Birds of the Adirondacks:

Mourning Warbler (Geothlypis philadelphia)

The Mourning Warbler (Geothlypis philadelphia) is a chunky warbler with a blue-gray hood and yellow underparts. It breeds in second-growth forests in Canada and much of New York State and New England, including the Adirondack Mountains.

The Mourning Warbler is a member of the New World Warbler or Wood Warbler family (Parulidae).

- The Mourning Warbler is part of the Geothlypis genus, which also includes the Common Yellowthroat. The Mourning Warbler is a former member of the genus Oporornis, but has been reassigned to the Geothlypis genus on the basis of DNA analyses.

- The Mourning Warbler was named by Alexander Wilson, an ornithologist, who shot the bird in 1820 on the border of a marsh near Philadelphia: Apparently the dark hood reminded him of 19th century mourning dress, because he later noted: "The singular appearance of the head, neck and breast, suggested the name." The species name (philadelphia) is also a reference to this early specimen's location.

- Other informal names for the bird include Mourning Ground Warbler and Mourning Yellowthroat.

Mourning Warbler: Identification

Mourning Warblers have olive-green upperparts and solid yellow underparts, with a blue-gray hood and relatively short tails. Their legs and feet are pinkish. Their bills have a pink base.

Mourning Warblers are average-sized for a Wood Warbler. An adult Mourning Warbler is 5.2 inches long, with a wingspan of 7.88 inches. It weighs in at 0.45 ounces.

The adult male Mourning Warbler in spring has a dark blue-gray head and throat with a black-mottled patch on his upper breast. The upperparts are olive and the underparts (including the lower breast, belly, and the area under the tail) a very bright, unstreaked yellow. In most cases, adult males lack an eye ring, but a small percentage have a very thin, white broken eye ring. Fall males are similar to spring males, but the crown has an olive-brown wash.

Adult females in spring are similar to their male counterparts, but are somewhat paler and lack the black feathering on the chest. Females may have a thin, light eye ring. Fall and winter adult females are similar to spring adult females, except for the fact that the head and upper parts of the bird are all olive or brownish with a yellowish or whitish throat.

Immature Mourning Warblers are similar to adult females, but show more olive-gray on the hood and an incomplete olive-gray bib. They usually have have a faint, broken eye ring.

There are several warblers that are similar to the Mourning Warbler.

- Most similar is the MacGillivray's Warbler, another furtive bird of forest edges and thickets. However, the MacGillivray's has a prominent, broken eye ring. More importantly, the breeding ranges of the two species do not overlap. MacGillivray's Warblers breed across the Pacific Northwest and the Rocky Mountains, and are not found in the Adirondacks.

- Another similar bird is the Connecticut Warbler. This warbler, however, has a bright white eye ring that contrasts with the broken, faint eye ring of immature Mourning Warblers. Moreover, sightings of Connecticut Warblers within the Adirondack Park are extremely rare.

- Nashville Warblers also have a much brighter eye ring than Mourning Warblers. They have a longer tail, finer bill and are more active in the low canopy, in contrast to the Mourning Warbler which is often seen on the ground.

- Immature Mourning Warblers may also be confused with female Common Yellowthroats. However, Mourning Warblers are more solidly yellow below, while Yellowthroats usually have a dull whitish pale brown belly region that contrasts with their yellow throat and upper breast.

Mourning Warbler: Songs and Calls

The Mourning Warbler's primary song is a series of two-syllable phrases, usually with two parts. The second pair of notes usually drops slightly in pitch. Most sources render the song as: "chirry, chirry, chirry, chorry, chorry." There reportedly is considerable variation in the song.

Only the male Mourning Warbler sings, presumably as an advertisement of its territorial and sexual status. Mourning Warblers are most commonly heard singing during the early part of the breeding cycle, from late May to mid-July. Frequency of singing declines during the nesting cycle, but usually doesn't end until after the young have departed the nest.

Singing begins about a half hour before sunrise, then declines after mid-morning. Singing intensity resumes early in the evening and terminates soon after dusk. Males are often heard singing from low in the underbrush, working their way to higher perches in the trees or shrubs.

The Mourning Warbler's call is a buzzy "chit." Its flight call is a thin, sharp "svit."

Mourning Warbler: Behavior

The Mourning Warbler is usually described as a shy, elusive bird. Except when the male mounts higher perches to advertise its presence through song, this bird spends much of its time skulking about low to the ground and hiding in tangled undergrowth. It usually hops rather than walks.

The Mourning Warbler's flight is fast and somewhat bouncy, with rapid wing beats. It is rarely seen in extended flights.

Mourning Warbler: Migration

The Mourning Warbler is a long-distance migrant that spends its winters in Central and South America. It is one of the last warblers to head northward toward its breeding grounds in the spring. Sources disagree on the route taken, with a few sources indicating that this bird crosses the Gulf of Mexico and others that these warblers take an overland route through Mexico and Texas.

The Mourning Warbler migrates relatively early in the fall. Sources do not agree on fall departure dates, with some indicating that departure from breeding ground starts early in August and others stating that the fall migration extends into September.

The timing of eBird sightings in the Adirondack Mountains reflects this pattern of late spring and early fall migration. Although eBird checklists reflect both the presence of birds and the presence (and attention) of birders, these checklists are an important source of information on bird arrivals and departures from a particular area.

- Mourning Warblers are comparatively late spring arrivals in the Adirondacks. Few Mourning Warblers show up in our region until the latter half of May.

- Mourning Warblers also leave our region for their wintering grounds relatively early. Based on eBird checklists, most Mourning Warblers will have departed our region by very late August or the first week in September.

Mourning Warbler: Diet and Foraging

As with other New World Warblers, Mourning Warblers feed primarily on insects on their breeding grounds. Their diet has not been extensively studied, but most sources agree that insects, insect larvae, and spiders are the main items on their menu during the breeding season.

Mourning Warblers forage most actively at dawn and dusk, primarily in the undergrowth a few feet from the ground. These warblers usually forage alone, rather than in flocks, gleaning anthropods from foliage. They reportedly also have been seen making short flights to catch insects in midair. They are said to remove the wings and legs of their prey before consuming it.

During migration and on their wintering grounds, the Mourning Warbler is omnivorous.

Mourning Warbler: Breeding and Family Life

Mourning Warblers nest soon after they arrive on breeding ground in late May and early June. They build their nests on or near the ground in dense vegetation. Clutch size ranges from two to five eggs. Only the female incubates the eggs, usually for 12-13 days. Both parents reportedly feed the nestlings. Young Mourning Warblers leave the nest 7-9 days after hatching.

Parental care of the newly-fledged birds may extend another four weeks. Data from the New York State breeding bird surveys indicate that fledglings were observed from 21 June to 19 August.

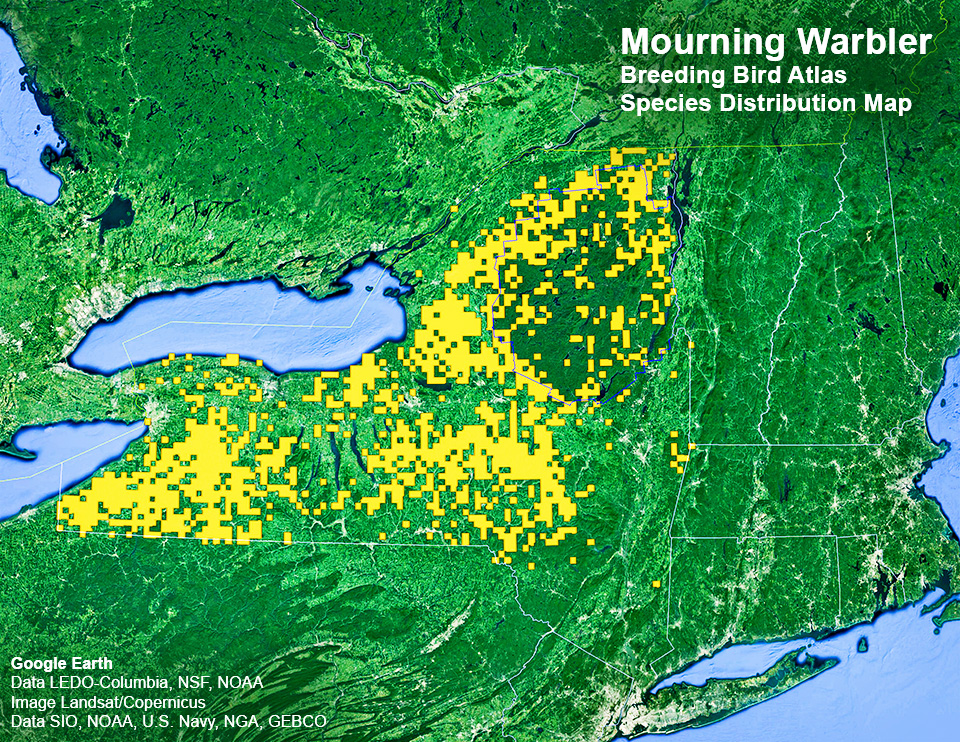

Distribution of the Mourning Warbler

The Mourning Warbler breeds from Alberta and extreme eastern British Columbia east to Newfoundland. In the US, its breeding range includes parts of New England, New York, and the Great Lakes region. There is an isolated breeding population in the Appalachian Mountains.

Mourning Warblers breed throughout much of New York State. The 2000-2005 Breeding Bird Survey indicated that breeding Mourning Warblers were concentrated in the northern and southwestern parts of the state.

- In the southern regions, breeding Mourning Warblers were concentrated in the central Appalachians, Cattaraugus Highlands, and Allegheny Hills ecozones.

- In the Adirondack region, breeding Mourning Warblers were concentrated in the Western Adirondack foothills, Western Adirondack Transition, and Tug Hill Transition ecozones, as well as the northern part of the Eastern Adirondack foothills and the High Peaks. Breeding Mourning Warblers were less densely scattered in the central Adirondacks ecozone.

Although sources disagree on the prevalence of the Mourning Warbler in North America (with some field manuals characterizing them as uncommon with others listing them as fairly common), Mourning Warbler populations appear to be secure.

- Partners in Flight estimates that the North American population of Mourning Warblers is about 17 million, with the vast majority (15 million) breeding in Canada. The Partners in Flight Landbird Conservation Plan noted a population decrease of 45% from 1970 to 2014.

- Because the Mourning Warbler prefers to breed in disturbed forests, they appear to have benefited from human activities such as logging and road building.

Mourning Warbler: Habitat

Mourning Warblers are an early successional species that nest in second-growth forests.

- Mourning Warblers colonize clearings with dense second growth caused by either human or natural disturbances, including logging, road building, fire, and winter ice storms.

- Mourning Warblers also breed in abandoned cultivated fields or forest edges and are often found in the brushy understory in dense tangles of bushes and young saplings.

Where to find Mourning Warblers in the Adirondacks

Adirondack Birding Sites for Mourning Warblers

- High Peaks

- Lyon Mountain

- West-Central Region

- Moose River Plains

- Wheeler Pond Loop

- Francis Lake

- Tug Hill Wildlife Management Area

- Northern Region

- Five Ponds Wilderness

- Massawepie Mire

- Azure Mountain

- Southern Region

- Pillsbury Mountain

- Sacandaga River's West Branch

Source: John M.C. Peterson and Gary N. Lee. Adirondack Birding. 60 Great Places to Find Birds (Lost Pond Press, 2008).

Adirondack birders in search of Mourning Warblers have a variety of birding sites to choose from, particularly in the northern Adirondacks and west-central regions, as listed in Peterson and Lee's Adirondack Birding guide. Their list of birding sites for Mourning Warblers includes the Moose River Plains and the Wheeler Pond Loop in Hamilton County and Massawepie Mire and Five Ponds Wilderness in St. Lawrence County.

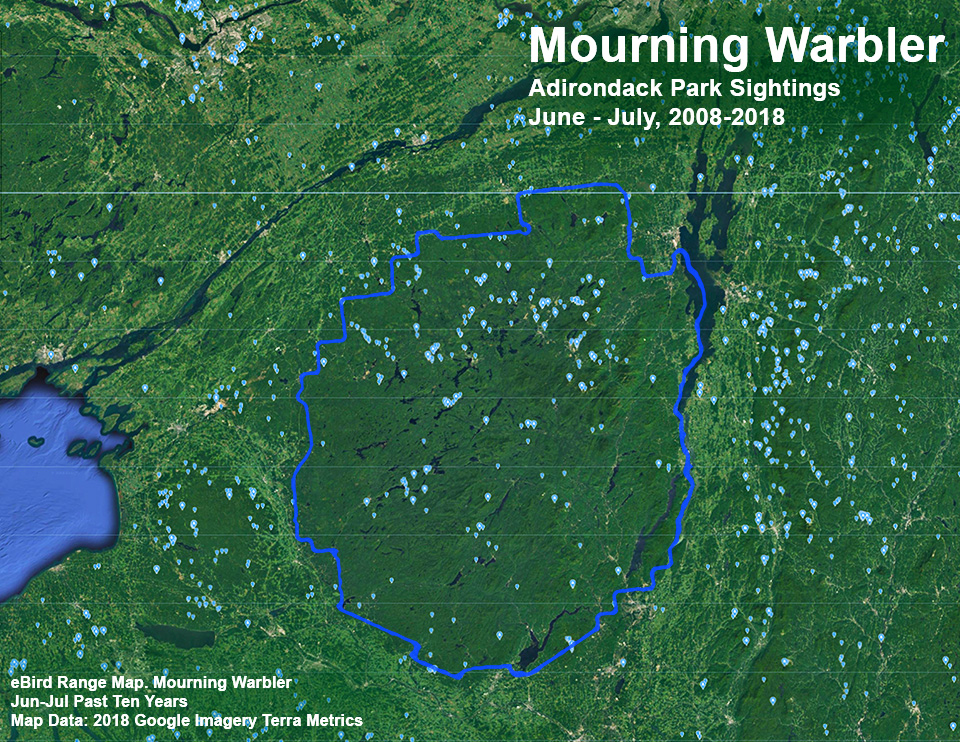

The pattern of eBird sightings for the Mourning Warbler during breeding season is roughly consistent with the findings of the two New York State Breeding Bird Surveys. Mourning Warbler sightings reported through eBird are more numerous outside the park than within the Blue Line, in part because there are more birders outside the Park and in part because the successional habitat favored by Mourning Warblers is more widespread in other parts of the state.

Within the Blue Line, Mourning Warbler sightings are scattered throughout the region, although sightings are most numerous in the northern part of the Park. There are clusters of sightings around the sites highlighted in the Peterson and Lee guide, including Massawepie Mire and Moose River Plains.

Among the trails covered here, the most likely locations to look for Mourning Warblers include the brushy areas on the edges of the fields at the John Brown Farm Trails and the second growth areas along the Logger's Loop Trail as it passes through the Forest Ecosystem Research and Demonstration Area (FERDA) plots.

References

American Ornithological Society. Checklist of North American Birds. Geothlypis philadelphia. Retrieved 24 January 2025.

Avibase. The World Bird Database. Mourning Warbler. Geothlypis philadelphia. Retrieved 24 January 2025.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. All About Birds. Mourning Warbler. Geothlypis philadelphia. Retrieved 24 January 2025.

J. Pitocchelli (2020). Mourning Warbler. Geothlypis philadelphia. Version 1.0 in Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. Retrieved 24 January 2025.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Macaulay Library. Mourning Warbler. Geothlypis philadelphia. Retrieved 24 January 2025.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Warren, Hamilton, Essex, Herkimer, Clinton, Franklin). Retrieved 24 January 2025.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Hamilton). Retrieved 24 January 2025.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Species Maps. Mourning Warbler. Geothlypis philadelphia. Retrieved 24 January 2025.

New York. Breeding Bird Atlas III. Mourning Warbler Species Map. eBird, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Retrieved 24 January 2025.

Xeno-canto Database. Mourning Warbler. Geothlypis philadelphia. Retrieved 24 January 2025.

USGS. Longevity Records of North American Birds. Mourning Warbler. Retrieved 24 January 2025.

Boreal Songbird Initiative. Guide to Boreal Birds. Mourning Warbler. Oporornis philadelphia. Retrieved 24 January 2025.

Audubon. Guide to North American Birds. Mourning Warbler. Geothlypis philadelphia. Retrieved 24 January 2025.

Bird Watcher's Digest. Bird Identification Guide. Mourning Warbler. Geothlypis philadelphia. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. Breeding Bird Atlas: Species Distributions Map (Google Earth). Mourning Warbler. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Breeding Bird Atlas: Species Distribution Map, 1980-1985. Release 1.0. Updated 6 June 2007. Mourning Warbler. Oporornis philadelphia. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Breeding Bird Atlas: Species Distribution Map, 2000-2005. Release 1.0. Updated 11 June 2011. Mourning Warbler. Oporornis philadelphia. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

New York State.

Joan E. Collins, "Mourning Warbler. Oporornis philadelphia," in Kevin J. McGowan and Kimberley Corwin (Eds). The Second Atlas of Breeding Birds in New York State (Cornell University Press, 2008), pp. 526-527, 640.

Charles R. Smith, "Mourning Warbler. Oporornis philadelphia," in Robert F. Andrle and Janet R. Carroll (Eds.) The Atlas of Breeding Birds in New York State (Cornell University Press, 1988). pp. 414-415, 517.

New York Breeding Bird Atlas III. Species Map. Mourning Warbler. Geothlypis philadelphia. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

Geoffrey Carleton. Birds of Essex County, New York. Third Edition (High Peaks Audubon Society, 1999), p. 38.

Charles W. Mitchell and William E. Krueger. Birds of Clinton County. Second Edition (High Peaks Audubon Society, 1997), pp. 18-19, 103.

Alan E. Bessette, William K. Chapman, Warren S. Greene and Douglas R. Pens. Birds of the Adirondacks. A Field Guide (North Country Books, Inc., 1993), p. 200.

John M.C. Peterson and Gary N. Lee. Adirondack Birding. 60 Great Places to Find Birds (Lost Pond Press, 2008), pp.88-90, 98-101, 105-107, 140-144, 166-168, 181-185, 190-192, 196-198, 211.

Adirondack Park Agency. Checklist of Birds of the Adirondack Park Visitor Interpretive Center at Paul Smiths, NY. Undated.

Sauer, J. R., D. K. Niven, J. E. Hines, D. J. Ziolkowski, Jr, K. L. Pardieck, J. E. Fallon, and W. A. Link. 2017. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2015. Version 2.07.2017. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

Sauer, J. R., D. K. Niven, J. E. Hines, D. J. Ziolkowski, Jr, K. L. Pardieck, J. E. Fallon, and W. A. Link. 2017. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2015. Trend Estimate by Species. Mourning Warbler. Geothlypis philadelphia. Version 2.07.2017. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

Vermont Atlas of Life. Vermont Breeding Bird Species Profiles. Mourning Warbler. Geothlypis philadelphia. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

Mass Audubon. Breeding Bird Atlas 2. Species Accounts. Mourning Warbler. Oporornis philadelphia. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas 1. Species Maps. Mourning Warbler. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas 1. Species Maps. Mourning Warbler. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

Minnesota Breeding Bird Atlas. Mourning Warbler. Geothlypis philadelphia. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

Partners in Flight. Partners in Flight Science Committee 2013. Population Estimates Database, version 2013. Mourning Warbler. Geothlypis philadelphia. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

Partners in Flight. Partners in Flight Landbird Conservation Plan. 2016 Revision for Canada and Continental United States, p. 110. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

Verne E. Davison. Attracting Birds from the Prairies to the Atlantic (Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1967), p. 141.

Margaret McKenny. Birds in the Garden and How to Attract Them (Grosset & Dunlap, 1939), p. 193.

David Allen Sibley. Sibley Birds East. Second Edition (Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), p. 347.

David Allen Sibley. The Sibley Guide to Birds. Second Edition (Alfred A. Knopf, 2014), p. 479.

Roger Tory Peterson. Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Eastern and Central North America. Sixth Edition (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010), pp. 280-281.

Donald and Lillian Stokes. The New Stokes Field Guide to Birds. Eastern Region (Little, Brown and Company, 2013), p. 362.

Jonathan Alderfer, Ed. Complete Birds of North America. Second Edition (National Geographic, 2014), pp. 602-603.

Richard Crossley. The Crossley ID Guide (Princeton University Press, 2011), p. 434.

American Museum of Natural History. Birds of North America. Revised Edition (Dorling Kindersley Limited, 2016), p. 579.

John Bull and John Farrand, Jr. Eds. National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds. Eastern Region. Second Edition (Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), p. 683.

Edward S. Brinkley. National Wildlife Federation Field Guide to Birds of North America (Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 2007), p. 366.

Tom Stephenson and Scott Whittle. The Warbler Guide (Princeton University Press, 2013), pp. 29, 33, 50, 97, 259, 262, 266, 272, 308, 310, 332, 334, 335, 338, 350-359, 362, 380, 389, 533, 536, 542, 547.

Chris G. Earley. Warblers of the Great Lakes Region & Eastern North America (Firefly Books, 2003), pp. 94-95. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

Frank M. Chapman. The Warblers of North America. Third Edition (D. Appleton & Company, 1907), pp. 244-249. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

Jon Curson, David Quinn and David Beadle. Warblers of the Americas. An Identification Guide (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1994), pp. 171-172, Plate 18. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

Jon L. Dunn and Kimball L. Garrett. A Field Guide to Warblers of North America (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1997), pp. 493-502, Plate 23. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

Douglass H. Morse. American Warblers: An Ecological and Behavioral Perspective (Harvard University Press, 1989), pp. 29-31, 57-89. Retrieved 7 April 2021

Alexander Wilson. The Natural History of the Birds of the United States. Volume 2 (Collins & Co., 1828), pp. 345-347. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp. 97, 125. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Sightings. Mourning Warbler. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

Aretas A. Saunders, "The Summer Birds of the Northern Adirondack Mountains," Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin. Volume 5. Number 3 (September 1929), pp. 333-334, 345, 354-356, 383, 433. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Theodore Roosevelt, "The Summer Birds of the Adirondacks in Franklin County, N.Y.," Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin, Volume 5. Number 3 (September 1929), pp. 501-504. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Perley M. Silloway, "Relation of Summer Birds to the Western Adirondack Forest," Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin, Volume 1, Number 4 (March 1923), pp. 436, 447, 477. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Elon Howard Eaton. Birds of New York (New York State Museum, 1914), pp. 16, 21, 27, 31, 448-452. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

George W. Cox, "A Life History of the Mourning Warbler," The Wilson Bulletin, Volume 72, Number 1 (March 1960), pp. 5-28. Retrieved 27 November 2018.